Freedom Summer In Mississippi Still Stands Out

Freedom Summer In Mississippi Still Stands Out

By Allen G. Breed

Freedom Summer in Mississippi still stands out as a watershed moment, fifty years later, in the long drive to achieve civil rights for African Americans. It was 1964 and mass resistance to integration started to crumble in the south. Congress took a monumental step toward equal rights. And scores of young, idealistic volunteers embarked on careers of activism that continue to shape American politics and policy today.

And in this vortex of history, lifelong friendships formed between people from vastly different worlds. So it was that a black 16-year-old from Mississippi, Roy DeBerry, and the 26-year-old daughter of a Jewish furniture mogul, Aviva Futorian, bonded over books and bologna sandwiches during a summer that would define their lives. To them, Freedom summer in Mississippi still stands out as a seminal event in their lives and that to the nation.

Years of demonstrations by determined local blacks, boycotts, legislative campaigns and bloody pitched battles had not dislodged segregation. On March 20, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which had been fighting for integration, announced the “Mississippi Summer Project.” The group concluded it needed a dramatic tactic to draw national attention to the injustices – and putting Northern whites in harm’s way seemed sure to accomplish that. Freedom Summer in Mississippi was how it became most known.

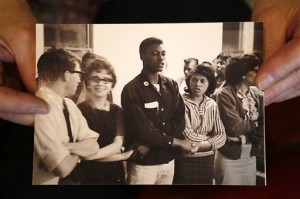

Freedom Summer in Mississippi still stands out. Photo Credit: The Associated Press, M. Spencer-Green, File.

Volunteers converged for training at a college in Ohio. On June 21, even before orientation ended, chilling word spread: Three young volunteers – New Yorkers Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, and Mississippi native James Chaney – had vanished while investigating the burning of a black church.

En route to Mississippi, the menace quickly became clear to Futorian. Following a gasoline stop in Tennessee, her car and its mixed-race passengers were chased for miles at high speeds. Finally, their pursuers gave up.

“I probably didn’t have as much trepidation as I should have,” said Futorian, now a 76-year-old attorney. “Because it’s hard to imagine your own death.”

Maybe it was because his grandparents had been landowners since just after slavery days, or because his father wasn’t dependent on sharecropping a white man’s land. Whatever the source, DeBerry had “an independent streak.”

He sensed the injustice of having to climb to the gallery at the segregated Holly Theatre. He resented having to call the white kid behind the counter at Tyson’s Drug Store “sir.” No one needed to teach you that,” the 66-year-old DeBerry said. “It was just something that was in your DNA.” So when a Freedom School opened in an unassuming white-frame building, DeBerry found his way there.

When Futorian – who’d teach at two Freedom Schools that summer – met with a group of black teenage boys, she asked them who were the richest blacks in town, how they earned their living, were they involved in the civil rights movement and if not, why not?

“Roy was the only one who knew the answers,” she recalls. DeBerry says this was his first interaction with a white person “on a social level.”

Through donated books, Futorian introduced him to James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright and other “subversive” black authors. They shared sandwiches at Modena’s Cafe in the “colored” section of town. They worked on voter registration – though separately.

They were well aware of the risks they were taking even before Aug. 4, when searchers dug the bodies of the three missing civil rights workers from an earthen dam.

That summer brought the beginnings of change in Mississippi and beyond. Systematic resistance to integration began fading in the state. Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which became law July 2.

And though fewer than one-tenth of the 17,000 black residents who attempted to register succeeded, the effort helped create momentum for the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Aviva Futorian and Roy DeBerry have remained life-long friends. Photo Credit: The Associated Press, M. Spencer-Green, File

Some believe this activism planted the seeds for history-making events generations later. “If it hadn’t been for the veterans of Freedom Summer, there would be no Barack Obama,” longtime Georgia congressman John Lewis, then a coordinator for SNCC, wrote in a memoir.

Rita Bender, Michael Schwerner’s widow, is less optimistic.

She says a refusal by some to recognize past inequities is partly to blame for today’s social ills. Now an attorney in Seattle, she’s dismayed at recent developments – a Supreme Court decision that nullified portions of the Voting Rights Act, voter identification laws, “stand-your-ground” laws. The country, she says, is “moving backward.”

Sitting side by side recently in Futorian’s condominium overlooking Chicago’s Lincoln Park, the two friends reminisced about lessons under a tree, practice sessions for a sit-in at a segregated theater, taboos that prevented a white woman and black man from sitting next to each other in a car.

The Associated Press, Copyright 2014

Featured Photo: Confederate Flag still flies at Courthouse in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Photo Credit: The Associated Press, Allen Breed.